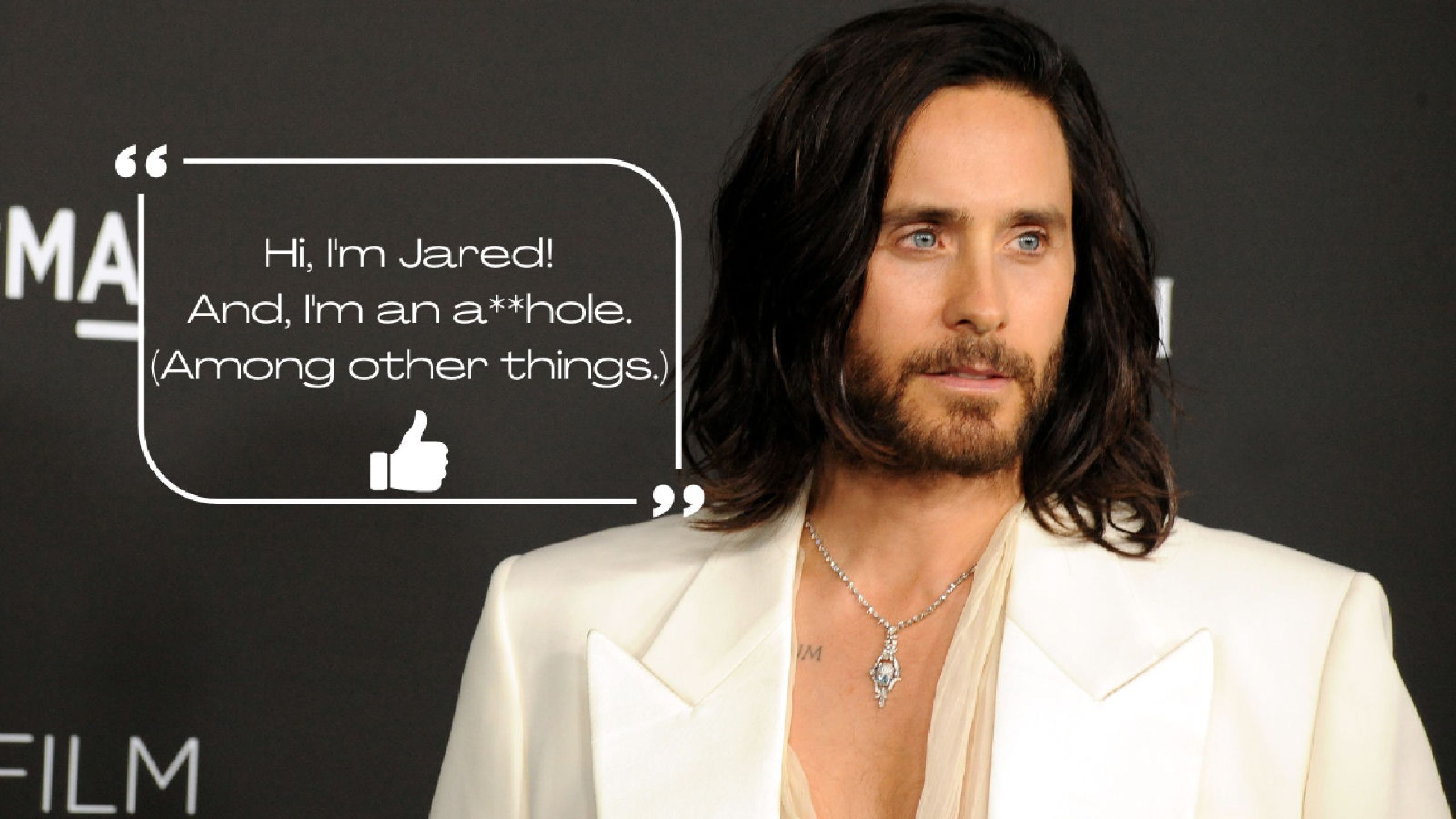

Jared Leto is, and always has been, an asshole.

Just to get that easy, unabashed fact out of the way. Having faced various accusations of assault, misconduct and all kinds of questionable behavior for decades, Leto has used his status as a celebrity to cultivate a near stone's throw allusion of a cult to those who - for reasons* - call themselves fans without understanding what they are getting into by attaching themselves anywhere close to his orbit. *Being in a rock band through most of the 2000's gets a lot of sway for a certain demographic apparently.

To keep this somewhat short in regards to the subject at hand, Leto's reported behavior on various film sets has been degrading on a number of fronts. At the very least, a nuisance. And at worst, contributing to a toxic and unsafe work environment. From harassing crew members to sending various inappropriate items to coworkers. (All of this can be looked up and researched on one's own time.) But the more horrifying aspect is that these actions and the actions of others, are carried out in the name of what they consider to be the "process of art". This is the method of their approach to depict their characters the best way that they can.

This is the method behind The Method, these days. And it's preposterous. In modern times, there have been more stories than one can count over the actions of actors conduct being detrimental to the workplace. Berating others, being more trouble than they are worth (like the aforementioned Oscar-winner) and hiding behind the well worn out excuse of "staying in character" to justify it all. Unfortunately, this has been the standard for so long that such misunderstandings might be hard to unravel in a serious way, with even the reaction and reconstruction starting off on the wrong foot. Actors are now coming out against this behavior (good!) by collectively affirming that one doesn't need to be an asshole to achieve a good performance (yes!). Others have gone as far as to say that these reports are exactly why they don't like The Method (no!). All of this is to say that clearly the true definition of what The Method actually is, has been lost. Most of the reactions are in response to the outlandish and frankly, idiotic situations that have occurred due to the perpetuated myths of what has long been considered to be The Method.

Let's start at the beginning, to see how we ended up in this unfortunate spot.

Basically, there is no one version or encompassing concept in the Method. There are different approaches, but the foundational notion of The Method is the attempt to achieve honesty through action. To use the emotional reservoir and memory of the actor to connect with and display the complexities and depth of the character conceived and written. Many acting teachers and masters had different ways to go about this. Konstantin Stanislavski believed that "the actor must think, act and behave truthfully as the character would go.". Sanford Meisner focused on overarching emotion, improvisation and script analysis, to disengage with themselves and embrace the character fully. (This is different from Stanislavski's method which was about engagement and the two differed on approaches here. One favored emotionality, the other favored imagination.)

There are more famous teachers, such as Stella Adler and Lee Strasberg. This all comes from a reaction to what had been the standard mode of acting in mainstream cinema. Derived from the theater; crisp enunciation, the faux Transatlantic accent that many spoke in to give characters a touch of class and nuance. The good old fashioned "arrive on time, don't bump into the furniture, know your mark and say your lines from the toes up" that actors such as James Cagney, Cary Grant and many others subscribed to. There was no notion of transforming yourself, emotionally or intellectually, when all that was going to be seen was external. (Not to say that there weren't actors working in something of that mode in Hollywood at the time of course; Bette Davis and Fredric March are two legends that come to mind)

That mostly changed when Montgomery Clift and especially Marlon Brando came to the forefront of cinema from the theater and The Actors Studio in the late 1940s to lauded heights of films in the early 1950s. Performances of theirs such as The Search, A Place in the Sun from Clift and Brando's otherworldly run of roles in A Streetcar Named Desire, Viva Zaputa, The Wild One, Julius Caesar, and of course the Oscar-winning depiction in On the Waterfront showcased such a depth and broiling storm of internal power that hadn't been seen in American theaters before. The electricity that came off the screen was (and really, still is) palatable in those performances, and changed the course of history.

But the thing is, Brando, Clift and their contemporaries didn't use their techniques or acumen as an excuse for being assholes on set or at work. Some actors definitely built a reputation, especially Brando, but it wasn't for the sake of performance. (Which, we can discuss another time.)

The first wave of the Method actors didn't stay in character. because it wasn't needed. Nor did they delve so much into "the research" of their characters that they lost a sense of themselves, doing actual harm to themselves or others accordingly. In fact, this is frown upon and even warned against in most depictions of The Method. (Brando himself hated being confused or misconstrued as being exactly like his character Stanley Kowalski in Streetcar) Alas, though, that's not where the problem stems from. The problem comes from the children of this era of acting, who would proliferate New Hollywood in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Brando, Clift, and others made such an impression and changed the DNA of American acting that the next generation in Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Jack Nicholson, Dustin Hoffman, Jane Fonda, Robert Duvall, Gene Hackman, Faye Dunaway and many, many more, took what they were enthralled by growing up and went even further than their predecessors. It wasn't enough to do the emotional, interior work of crafting the character, but wouldn't it make sense to actually do what that character does for an even more honest performance? This was especially the case with De Niro, who would learn Italian and intensely study every movement of Brando's Vito Corleone to craft the younger version in his first Oscar-winning performance in The Godfather, Part II. He would actually drive cabs around New York City for a few weeks to get into the nocturnal routine and mindset of Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, and of course his famous weight gain to play the self-destructive pugilist in his second Oscar winner, Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull. To say that these performances have cast a long, wide shadow and massive influence over acting since then to generations that came afterwards is an understatement. But hearing these stories of what De Niro and others did to get to that point where they achieved awards and notoriety, the lesson wasn't "that was his own personal initiative to getting to where he needed to go" but instead "that's what I have to do to win awards and give as good as they did."

This becomes more underlined and calcified when the most revered actor of his generation afterwards, Daniel Day-Lewis, took this even further when his stories started to filter out on his most celebrated performances. Staying in his wheelchair and being helped around by the crew on My Left Foot, learning how to build a canoe and living off the land for a time on The Last of the Mohicans, even becoming a cobbler in Italy and not taking certain medicine when sick because it didn't exist in the time period his character lived in for The Cobbler and Gangs of New York respectively. To his credit, Day-Lewis didn't like to dwell on these stories and emphasized when asked about them that this worked for him and him alone. Unfortunately that wasn't the takeaway for everyone else. Especially when stories such as these do more expressing and talking of their approach than the reclusive actor does for himself.

Are these noted performances some of the best and memorable of their times? The consensus is an overwhelming yes. However, are these measures worth taking to achieve those heights? That seems to be the question. A question that no one seems to be asking, as the ends don't seem to justify the means much anymore. Not to say that staying in character and what that comes with cannot deliver great performances - of course it can and still does - but that doesn't mean it justifies the indulgence of such behavior of that of Leto's or others who have been reported on in the same way.

It almost seems like such juvenile acts are the point for some actors: to get some press and ink for the attention they are seeking, and not for actually doing the work to craft something unique and everlasting. All of this has brought a loud and unfortunate misunderstanding on the work that many have done to bring The Method and its different variations to the forefront of acting. The point of The Method isn't to be seen in such a way, but what is seen of the end result. But if all that is being seen and heard is the nonsense that has been strained to this point over time, than what else is there than to yell about the actions of bad actors?

In the often told infamous story about what Sir Laurence Olivier said to Dustin Hoffman on the set of Marathon Man. Where Hoffman played a character that was exhausted, so he stayed up for three days straight to actually be tired and portray that realistically in his performance. Olivier just looked at him when he stumbled onto the set and asked the very important question of "why don't you try acting, my dear boy?"

Sounds like a great question that needs to be asked more often these days.